In 2021, I served as the Director of Operations for the University of Texas at Austin's flagship interdisciplinary rocket engineering lab, TREL. The position is effectively the student-lead for the two-year-old, 200+ member lab of undergrads and graduate students from all majors with all the makings of a CEO position at a startup – lots of unstructured time, managing long-term risks, strategizing workflows, fighting fires, aligning internal & external stakeholders, and managing recruiting. I had hoped that it would be more of a Product Manager-esque role, focusing on planning, procurement, and execution of the project (in this case, a 32+ ft rocket). Much of the work was administrative and busy however, and I worked hard to ensure there were systems in the lab setup to handle the scale it had rapidly achieved (5 to 200+ in <2 years!).

A bit more background before I launch into my learnings from the experience: I was an engineering lead within the lab for about nine months prior to my stint as Director of Ops. It was frustrating, to say the least, and a combination of growing pains, scaling too quickly, and COVID-19-induced remote-work convinced me, for some reason, I was the right guy for the job.

In TREL, leadership roles turn-over about every year – the lab itself is a high churn environment, with about 20% membership attrition yearly built in: people graduate and get real jobs! In the end, I'm not sure I contributed more than I took – I would attribute the majority of my impact to a steadfastness and an eye for the long-term health of the lab, primarily concerning leadership transitions and continuity. But I digress; let me now bore you with what the lab gave to me.

What I learned from a year as CEO/PM of a Collegiate Rocket Engineering Lab

Initiation Euphoria

When a project, company, clever engineering assembly – anything that is just a few hours beyond scribbles on a napkin or some exciting conversations – begins, the mood is doomed to be elevated above the looming constraints of reality. It *will* come back down, aspects of the project *will* fall short from what is established in the early conceptualizations. It is incredibly important to acknowledge this from the start and organize your approach to mitigate the momentum you will lose in the future. Personally, I believe that this is the best takeaway of them all and coincidentally it's no. 1 on this list (none of the others are ranked, it's the order I thought of them). Initiation euphoria is a double-edged sword – it's the reason we lose so many good ideas to entropy and it's the reason why *a "day-one mentality"* is critical. If you've convinced a smart, capable team that every step of the project journey is an exciting opportunity to explore and create, that's 80% of the battle.

Initiation euphoria can hit particularly hard if the individuals who were initially excited by a concept do work to outline it and then subsequently trickle out of an organization before said concept is realized. Paired with a rapid pace of onboarding and an inconsistent training system, this can be a lethal mixture. A key strategy here is to constantly outline and review expectations, disseminating them as exhaustively as possible within the project team – one of the best ways to reign in unrealistic expectations is to communicate them as clearly as possible in the first place.

Bottom line: Communicate a clear vision, as to pull people into day-one mentality, everyday.

Respect & Highlight People

People are the decentralized agents of success (process is the centralized agent). When leading a project or an organization, it is important to cultivate "informal authority." You want people on your team to work with you, not against you. Informal authority is just ability to motivate people: it's there until it isn't. It's there when inspired through character and integrity; it's absent when apathy and dishonesty are perceived. I think there are a few key actions you must take to be a superior team player here.

- Talk straight – honesty is an important form of respect.

- Listen – respect is hearing feelings, motivations, frustrations, dumb jokes.

- Clarify Expectations – people are excited, engaged, and confident when it is clear they are making a contribution.

- Broadcast – show your team that you know them by highlighting accomplishments; be willing to admit your own mistakes.

Bottom line: People on your project are people first.

Cone of Uncertainty

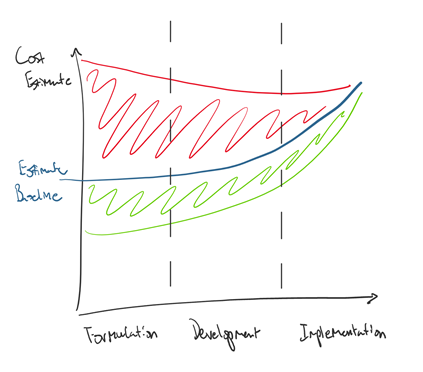

This is a rather intuitive one – the precision of a cost estimate ($, effort, capital, etc.) is inversely related to the % completion of the project and will almost always present as an underestimate (see: initiation euphoria). Visualized, that looks something like this:

The Cone of Uncertainty, where the green and red regions represent under and over estimates, respectively.

Besides the higher-ups demanding certainty in estimations (and here I think you just have to be honest about your unknowns/knowns), this is hardly a big deal in itself – it's always the case. Dealing with this uncertainty requires rigorous accountability:

First, you need to identify the risks with your team and classify them by probability and impact (i.e. how much will it cost). Then, you either transfer, accept, mitigate, or eliminate the risks.

An aside: This is also a great time to lock-in your team and discussing risks is always a fantastic opportunity to give everyone a chance to speak their mind and give you the chance to assess who's effort is best spent where. It also drives buy in, which is key for moving into later stages of project implementation as efficiently as possible.

Finally, you create consistent accountability metrics surrounding relevant risks/uncertainties that are updated as the project moves forward. Be flexible here! New information makes this necessarily a closed loop.

Uncertainty and accountability go hand-in-hand – there **must** be a feedback mechanism between commitment and completion as the team cuts through the fog of uncertainty. This can be as simple as brief sessions updating expectations in various risk/cost buckets; just don't let a single uncertainty slip.

Bottom line: Pervasive, constant uncertainty is countered by exhaustive, consistent accountability.

Stakeholder Involvement is Key

I helped to clean up a pretty nasty mess with a key stakeholder in my first few months in the position, and it shaped my agenda for the remainder of the year. Nearly everything I worked on, from internal tag-ups to key project decisions, was done with stakeholders in mind. I assumed nothing was clear until made otherwise. This is where I've seen projects go sideways: you cannot assume you know anything about a stakeholder, and you absolutely cannot assume a stakeholder knows anything about the project. Here, in particular, information must be spoon-fed with the greatest of care.

When initiating a project, it is critical to exhaustively identify the stakeholders involved. Without doing so, the project can stray dramatically from their expectations and well beyond their limitations – you must create a shared understanding of project outcomes, regularly & clearly communicated to all groups, and you must constantly make decisions juggling the desires and limits of all groups. This is no easy task, and it begins before a project even starts. Neglect no group, certainly not those with the ability to throttle a project's pace & energy – stakeholders like donors and project team members come to mind.

Bottom line: Stakeholder engagement exponentially increases chances of success and puts a floor on failure.

Always Explore

Constantly ask yourself: "What am I not doing." Look to other leaders, within and without your organization for inspiration – at the top, you should always be seeking ways to raise the bar and elevate those around who do so naturally.

One of the most enjoyable aspects of the position was exploring the potential directions to take future projects or the potential for future collaborators (other student rocket labs, corporate partnerships, events in Austin). While there is value in steadiness, there is so much *fun* to be had in exploring. Importantly, giving people room to explore is one of the best ways to ensure an organization or project does not stagnate and that people enjoy themselves.

There is a caveat to this: scope creep or an unfocused team is generally unacceptable.

Bottom line: Seek novelty with your eyes on the prize.

Traceability – Connect the Dots

Your team is doomed if you cannot implement some sort of version control **and** an effective way of documenting technical knowledge. Why? Because people forget things & teams change. I didn't fight this nearly as well as I wanted to in the lab, and while it is a good thing to have an ever-expanding network of somewhat involved & knowledgeable people (i.e. graduates with real jobs), it is a nasty thing to have 20%+ attrition built-in. Your teams end up burning a ton of time as new people in charge ramp into the role *and* retread the same ground already trod. It's painful to witness. One thing that I worked initially to implement was readability of documentation – hoping to standardize something like a centralized information repository, a TL;DR at the beginning of wiki pages, a non-redundancy rule like SpaceX has – most of that was fruitless because it is difficult to implement a top-down solution to a team of 200 students. It just is. Or maybe I didn't try hard enough. A lot of the traceability in my organization has to come from the bottom-up, which translates to buy-in from contributing members. Build a team spirit on that.

I cannot overstate how difficult a problem this is to be reckoned with. It is a wicked problem, in that it becomes increasingly important to increase traceability as complexity scales, which makes doing so increasingly more challenging. A robust yet flexible schema for traceability is an absolute requirement for a long-term success. The two bits of advice I have here are

- The importance of buy-in from the membership & leadership on a given documentation strategy

- Continuity of expectations and problems. Let nothing fall off, let nothing on the boat without first careful review.

Bottom line: Ask yourself how easy things would be if everyone on your team got amnesia overnight. Probably pretty tough, right? Fix that.

Clarify Expectations and Rigorously Define Problems

This is more of a lesson in engineering than management, but the golden rule in systems engineering is never to let the solution you have in mind lead you to the requirements for a problem. This constrains creativity and will ultimately overcomplicate the entire project.

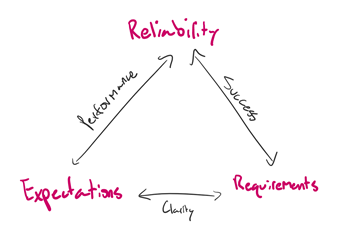

It is paramount to instead develop a clear, well documented understanding of any problem and develop requirements for a solution based on that understanding. Requirements **are** rigorously defined problems. This will allow for the subsequent articulation of clear expectations that are traceable to a specific aspect of whatever problem you are trying to address. It's an iron triangle of responsibility – take any of the legs away and your team won't be able to generate the clarity, performance, or finalization it needs to complete a project.

Triangle of Responsibility, with legs depicting elements inspired by the connecting vertices

As usual, the importance of this scales with complexity. Defined problems, clear expectations, reliable output.

One of the interesting applications of this rule is one I found in dealing with implementing standards of procedure for the sake of continuity in a student lab: rigorously defining a problem arising from something procedural like procurement is the **best way** to clearly communicate the expectations for a successful outcome.

Bottom line: Requirements and expectations are two sides of the same coin. Make sure it is out in the open & not vaulted away somewhere!

Embrace Struggle – Failure is the Recipe for Success

One of the systems I worked to put in place – a dynamic, centralized schedule – was only the success it was because of how many times it didn't work. I took the wrong approach for about a semester, but I learned a great deal in the process about the importance of consistency and some of the pitfalls of delegation (namely, output is inconsistent and scope creeps). Several smaller pockets of subteams (mostly engineering ones) had independently developed task tracking processes with a similar effect, only issue was they were entirely local. One of the keys was absorbing the successes locally and working to implement features of these processes at scale, giving the implementation the flavor and efficacy of a bottom-up system. That, and a couple of individuals with a penchant for giving good feedback and taking initiative. Smaller groups within an organization are like cauldrons, mixing and testing little things that might work at greater scale; you are required to pay attention to them and create the measurability needed to understand what a failure is & isn't.

Sometimes failure can lead you to an entirely new approach or a pivot altogether – it's important to be receptive and watchful for the alternative path to success. Generally though, if you are not failing, it's a signal that you are not making enough effort to push the boundary of accomplishment. Don't fall into that trap.

Bottom line: Don't conflate failure and giving-up.

Make Reversible Decisions Fast. Be Fast.

This goes hand in hand with the previous observation on learning: success is an opaque process that almost certainly requires iteration on the initial approach. In this way, achieving it for anything becomes a feedback loop, of both the positive and negative variety. Like anything else you do, there is a finite amount of time to solve for a success, and the speed at which you arrive at a solution is often dominated by two things.

First, how long are you waiting to undo bad decisions? How long does it even take to know they were bad? Establishing an initial threshold for reversibility is crucial. Too often, I would make decisions in the way of planning and processes that just would not work, yet I failed to iterate on them. Don't leave bad decisions to rot on their own devices.

Second, how fast are you making decisions? Only take on this tenet if the first has been properly addressed (!!). Decision making should be a nimble process, taking a minimum of everyone's total time. It should be a means to an end, not an end itself. In engineering, we can often get caught up in trade studies of various design approaches – resist the urge to spend tons of time here and keep an eye on the finish line.

A caveat: the speed at which a decision is made should vary roughly inversely not with its complexity, but its **reversibility and measurability**

Bottom line: Iteration is doing [insert thing] right now! GO! Why are you still reading this!?!

Beware of Management & Technical debt (scale w/ communication & process in mind)

The concept of management debt is something that I became immediately aware of stepping into my position in the lab. Similar to technical debt, like borrowing time by writing quick code or bad documentation, this is the practice of several transgressions including:

- Multiple people sharing decision making & accountability

- Not creating performance management or feedback processes

- Rotting, spotty, or simply non-existent lines of communication, especially abstracting general contributors from overarching project expectations.

My lab was guilty of all of these things, primarily because over the course of the two years since its inception, it scaled from about 5 members to 220, taking on management debt heavily from 60+ people. The best way to handle this is simply not doing it: awareness goes a long way and carefully scaling an organization with specificity in process & communication design is key. Pretty much everyone in the VC/Start-up world knows this, and for good reason.

If this is unavoidable, the best thing to do is to start chipping away at this debt – only now, you have a group of frustrated individuals to build off. I tried to use that to my advantage by listening and building a mental map of the missteps (silo-ing groups, confusing dual-leadership structures, lack of overall performance accountability rigor) and being as surgical as possible with my solutions (implement precise changes with consensus and be as loud as possible about it).

Bottom line: Technical debt will rot your organization from the inside (see: Traceability). Management debt will tie your hands at critical times.

Training & One-On-Ones are a 10x+ Return on Time

There is almost nothing more frustrating than being a new member on a project yet knowing almost nothing about how to get started. This happens so much more often than it should, or at least new contributors are inescapably left with gaps in their knowledge. As a leader, it is all too easy to make this mistake, especially when concerned about the technical soundness of a project. Make sure that your leadership has a mindset for investment, as this will foster long-term thinking and an emphasis on exhaustively orienting new members. *Everything depends on this.*

From my position, I worked to develop a robust contributor feedback system and had a great team implement and iterate upon it. If leadership is not aware of the status of contributors, this is extraordinarily bad. I also worked to develop a more consistent and exhaustive lab-wide training for new members (being back in person when we could in the pandemic helped a ton) where I could literally see people making better contact with the lab. I hosted new member orientations in our primary workshop – where hands-on work happens is the best place to show people that they *can* engage. I don't know if either of these have true staying power, but introducing strong cohorts of contributors and subsequently growing them obsessively is the only engine that will launch an organization into true greatness.

I think my bottom line here says it best.

Bottom line: When you work on a project, you should be investing, not working.

I missed some things, but this list is already way too wordy. If you're working on a project and found this list useful, reach out! I'd love to share and learn more about what interesting project woes remain lurking.